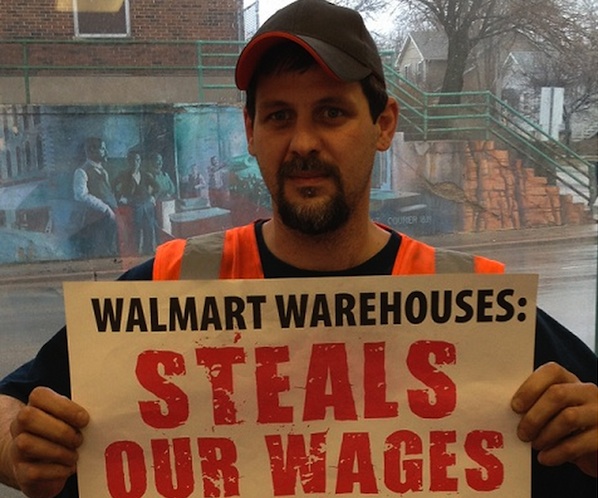

Mike Compton, one of nine workers fired after protesting alleged wage theft at Walmart's Elwood, Ill., warehouse, won back pay and vindication this week. (Warehouse Workers for Justice Facebook)

Workers in Walmart’s vast fulfillment network who say they have been treated illegally at work have gotten some good news for the holidays. Last Monday, just days after a Walmart contractor agreed to pay out $4.7 million for alleged wage theft to more than 500 warehouse workers in southern California, the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) secured a settlement over illegal retaliation against employees at the retail giant's distribution center in Elwood, Ill.

Nine workers affiliated with Warehouse Workers for Justice (WWJ)—a Joliet, Ill.-based workers center backed by the United Electrical, Radio and Machine Workers of America (UE)—who alleged they were fired for workplace organizing will receive a combined total of $52,381 in back pay, according to WWJ.

“It came at a good time,” says Mike Compton, one of the fired workers. “All nine of us needed it. Some of us were getting in pretty tight spots.”

Both the Illinois settlement and the California agreement are with the same Walmart contractor: Schneider Logistics, which operates many of the retailer’s warehouses around the country. (In the Illinois case, the NLRB also implicated two staffing agencies formerly used by Schneider at the Elwood distribution center: Roadlink Workforce Solutions and Skyward Employment Services.)

Over the past four years, workers in Walmart warehouses have filed lawsuits and held strikes in response to what they say are poverty wages and unsafe working conditions. The warehouse workers often earn only minimum wage and do not receive benefits; plus, they say, they work more hours than they are paid for, labor in extreme temperatures and lift boxes that weigh up to 250 pounds.

The new settlement concerns a 21-day strike staged by three dozen workers at Walmart’s distribution center in Elwood. The walkout began in September of 2012 when a group of workers was disciplined after presenting concerns about wage theft to management. The strike culminated in a large civil disobedience action that saw 17 arrests.

The strikers were allowed to return to work with full back pay for the days they had been out. The next month, however, nine of them were fired. Several of the firings occurred immediately after workers handed management a petition demanding an end to wage theft, discrimination and retaliation. Compton says that ten minutes after he and his coworkers delivered the petition, a manager told them they were being “taken out of service” and to go home. The next day, Compton says, his employer called him and told him not to return to work. In December 2012, the workers brought charges of illegal retaliation to the NLRB, which led to Monday’s settlement.

As part of the settlement, Schneider, Roadlink and Skyward must inform current and former employees of their right to take collective action under the National Labor Relations Act and pledge not to retaliate against those who organize, according to WWJ. However, because the two staffing agencies’ contracts with Schneider expired at the end of April, the nine workers will not be reinstated.

WWJ notes that swifter action by the NLRB might have restored the workers’ jobs. The NLRB finished its investigation and issued a complaint in March, and could have taken immediate action to reinstate the workers through a 10(j) injunction before their staffing agencies’ contracts expired, says WWJ spokesperson Leah Fried. She tells Working In These Times that the NLRB is “very timid when it comes to enforcing workers’ rights in organizing settings.”

Fried also notes that the case dragged on because the NLRB wanted a consolidated settlement with all of the companies involved. The staffing agencies settled quickly, she says, but the Board refused to issue the workers their checks until after Schneider also settled.

The case and the difficulties reaching a settlement highlight the Byzantine structure of Walmart’s supply chain. Walmart hires logistics companies like Schneider to operate its distribution centers; these companies in turn frequently hire staffing agencies to handle labor. Sometimes, the staffing agencies subcontract to other staffing agencies.

The layers of subcontractors allow Walmart “to wash their hands of problems in the warehouses,” says Compton. “It’s ultimately their building, their trucks in the parking lot, their freight, and it’s their computer software that we run. They need to take some responsibility for the conditions in their warehouses.” Both Compton and Fried say that repeated, egregious violations at Walmart’s distribution centers show that the company does not take seriously its own Standards for Suppliers—which include the freedom of association and collective bargaining.

Walmart store associates around the country have also alleged retaliation for recent organizing. In November, the NLRB issued a complaint against Walmart saying the company had illegally fired or disciplined store employees in multiple states for participating in a series of high-profile strikes and protests over the past year.

Compton says he has met many store associates through WWJ’s partnership with OUR Walmart, the union-backed workers' group that organized the retail actions. Now he gives more thought to the workers who unload the freight he packs onto trucks. “Either directly or indirectly, we work for [one of] the most profitable corporation that’s ever existed [and] we’re treated like we’re nothing,” he says. “In retail and in the warehouses, we really all are fighting for the same things: the end to retaliation and just basic respect on the job.”